- Home

- Collin Van Reenan

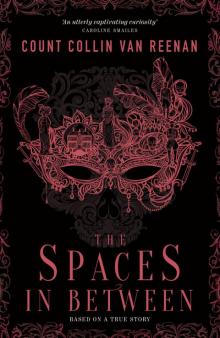

The Spaces in Between

The Spaces in Between Read online

COUNT COLLIN VAN REENAN

THE

SPACES

IN BETWEEN

Published by RedDoor

www.reddoorpublishing.com

© 2018 Collin Van Reenan

The right of Collin Van Reenan to be identified as author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

ISBN 978-1-912317-95-0

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, copied in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise transmitted without written permission from the author

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Cover design: Patrick Knowles

www.patrickknowlesdesign.com

Illustrations on pages xvi and xvii drawn by Graham Larwood

Plans on page 12 provided by Danny Hope of Hope Design Studio Ltd

Typesetting: Tutis Innovative E-Solutions Pte. Ltd

To Sue, without whom nothing would be possible

‘Every man has reminiscences which he would not tell to everyone, but only to his friends.

‘He has other matters in his mind which he would not reveal even to his friends, but only to himself, and that in secret.

‘But there are other things that a man is afraid to tell, even to himself, and every decent man has a number of such things stored away in his mind.’

Dostoevsky, Notes from the Underground

Some people may consider this is a ghost story; others, like my father, a crime. Some would say that it describes the relentless descent into neurosis; others that it is the greatest love story they know.

Marie-Claire Gröller, Paris, 1970

Preface

‘This is one of those cases in which the imagination is baffled by the facts.’

WINSTON CHURCHILL

My name is Marie-Claire Gröller, Doctor of Psychiatry. I deal with the neurotic, the psychotic and even the psychopathic, and I have many strange tales to tell; but none so utterly mysterious as the facts related in the following pages.

Normally (not a word that figures often in my profession), the rules of patient confidentiality would prevent such a story from ever leaving my files. There are, however, exceptions. In the case of dire need of the patient and with his full consent, it may be permitted to publish such details in the desperate hope that it may bring relief and closure for him.

In this case the patient is, moreover, also my friend.

His steadily deteriorating condition has forced me to take these unusual steps. Someone, somewhere, knows what happened, and could, if he or she had the courage to come forward, bring some sort of respite to a man who has suffered a great wrong and who is slowly sinking under the despair of not knowing why.

I first met the man (whom I shall call Nicholas) in late October 1968. After I qualified from the Sorbonne in Paris and spent two years at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, in 1968 my parents helped me to open my own practice in a small town called Rueil-Malmaison, about fifteen minutes by car from the centre of Paris to the north-west, across the Seine and behind the beautiful Bois de Boulogne Park. The town was already well served by consultants in all aspects of medicine, and at first I struggled to find work. Patients are most often referred to psychiatrists by general practitioners, and they preferred established and experienced colleagues. There was also, at that time, a certain amount of prejudice against women in the medical profession.

Fortunately, a young doctor close to my own practice was very helpful to me (we later married) and sent me my first patient.

My father was a commissaire de police, a high rank in the police judiciaire, and used part of his retirement pension to set me up in practice. My cabinet or practice was rather humble, consisting simply of two rooms above a lingerie boutique on the Rue Paul Vaillant-Couturier, a few yards from the church where the Empress Joséphine is entombed. The first room, furnished only with a desk and filing cabinet, served as the reception, and the second, with just two armchairs and a small table, as my practice room. I had to act as my own receptionist and answer the telephone to make appointments.

It was nearly a week before I received my first call. Dr David wished to refer a young man. The patient claimed he was suffering from insomnia, but the doctor suspected he was in fact clinically depressed. This young man, who lived nearby, was not registered locally with any doctor and had asked Dr David merely for a prescription for sleeping tablets. However, his appearance, lack of appetite and general state of health suggested to the good doctor that the problem was in the mind rather than the body. Dr David warned me that, although his new patient had reluctantly agreed to see me, he was very reticent and wary when asked about his background.

Trying not to sound too eager, I arranged an appointment, and 10 a.m. the next day found me peeping surreptitiously through the blinds on the street side of my rooms. When the bell sounded, I felt a childlike and inappropriate excitement, and wondered if perhaps I should be consulting someone myself!

Heart racing, I admitted my first private patient and led the way upstairs.

It was only when we found ourselves next to my two armchairs that I really had a chance to look at my client. He waited politely for me to sit, and that gave me a chance to observe him. My first impressions were of a man about twenty-three or twenty-four years of age, of medium height and build. I also noted that he was wearing an expensive, elegant if rather shabby dark grey suit, beautifully cut but in a rather old-fashioned double-breasted style, which seemed to hang on him as though he had lost some weight since it was made. Unusually for the times, his hair was short – brown, wavy, but with some premature greying at the sides. The shape of his face, together with his fair complexion, suggested that he was a northern European. His deep-set grey eyes were ringed with dark shadows that suggested lack of sleep.

Uneasy at my perhaps too obvious scrutiny, he fidgeted, eyes on the floor; but then he looked up suddenly with a shy smile and I glimpsed – again unusually for those heavy-smoking, coffee-drinking times – perfect white teeth.

Introducing myself and explaining Dr David’s concern, I asked him outright if anything was troubling him. He fidgeted uneasily again and refused to meet my eyes. Finally, he said that he was unable to sleep well, following an ‘unsettling experience’ a few months previously. His appetite also seemed to have deserted him and he felt unable to relax. He lived alone and was currently unemployed, living on an allowance sent to him by his parents.

As I listened to his soft voice, I noted that his French was clear and his pronunciation precise – an educated French that was, I thought, very good. In fact too good; I was listening to someone who was not speaking his mother tongue. I looked again at the name on the file I had just created – ‘Nicholas Van R.’ – and assumed that I was dealing with a Belgian, from Flanders. When I enquired, however, he told me that he was in fact English, though his mother was Irish and his father’s family had connections in South Africa.

I continued to probe and learned that he had come to Paris aged thirteen because his mother wanted him to be educated in France. At first he had boarded at the Lycée Henri-IV, afterwards spending a couple of years at the University of Liège, Belgium, where he had relatives, and then about two years ago had started a humanities course at the Sorbonne, with the intention of becoming a journalist. The first year, he had studied existentialism under Professor Paul Genestier, whom he greatly admired, but in his second year his tuition was taken over by Professor Robert S.– H.–, who, although he treated him well, was not someone Nicholas had been able to warm to.

He stopped suddenl

y and looked up at me; again that shy smile.

‘You were going to tell me about your “unsettling experience”…’ I prompted.

‘Well…’ He hesitated. ‘I’m not actually sure it’s relevant…’

‘Please go on.’ I smiled back. I could see we were getting closer to the problem and I needed to keep the momentum going.

He was uncomfortable now and again refused to look at me. When he was not smiling, his face appeared gaunt, and the dark shadows around his eyes made him look older than his years.

‘Please… Nicholas, if I may call you that… I can’t help you if you don’t explain…’

Slowly, he began to resume his story.

‘Well, it all started to go wrong – for me, that is – just at the start of January of this year. My parents retired to South Africa, but for some complicated reason their bank accounts were frozen…some business court case, I was told. Suddenly, my allowance stopped. I didn’t have much in the way of savings but I found some evening work as a plongeur in various restaurants and was just about managing…by making all sorts of economies. But…’

He looked up at me.

‘But I didn’t have a work permit and, when my student visa expired in March, I didn’t have the funds to show to get it renewed. I was unhappy with my classes…I hadn’t taken to Professor S.– H.–, as I said, and I had problems meeting my rent. The final straw was the outbreak of the student riots in May. There was a lot of damage…the restaurants closed and I could no longer earn money. I lost my rooms and had to doss down with friends…I even stayed with the Professor, just for a few days, that’s how desperate I was. I think I lived on cafés au lait for a couple of weeks. Then –’

He stopped abruptly, and it was obvious that he was approaching something that made him uncomfortable.

‘Please go on, Nicholas. I’m here to listen.’

He looked hard at me, as if trying to decide whether he could trust me, looked down at the floor and then, very slowly, raised his eyes to mine, made his decision and began, haltingly, ‘Then Bruno…a friend…found an ad in Le Figaro…for an English tutor…to live in. It seemed the only answer…the police were after me for overstaying my visa – you know, they threw all the foreign students out after the riots. Well, anyway, I took the job…in this really strange house…with an even weirder family.’

He stopped again and I was shocked to see tears running down his face.

‘And then – then that’s when it started.’

He stopped, unable to speak, and to hide his embarrassment stared rigidly at the floor. It was obvious to me that if I pressed him further it would only be detrimental to his confidence.

After a while, I said gently, ‘Look, Nicholas, I hope to be able to help you but I need to know the full details. I can’t promise you a “quick fix” but we have plenty of time. I’d like you to make another appointment to continue our chat –’

‘I don’t think I can talk about it, doctor…’ he broke in, agitated. ‘It’s too long and complicated and you won’t believe me anyway – no one does.’

I could see there was no point in continuing right now, so I suggested a tried and tested, if unimaginative, approach.

‘Well, Nicholas, we will meet again next week, and in the meantime I would like you to write down all the details. Write it all down. It’s important that you don’t leave anything out. Do you understand?’

He nodded without looking up.

‘Now, has Dr David given you any medication?’

He shook his head.

‘OK. I’m going to prescribe something for you, just a mild sedative, but you must try to eat regularly and get plenty of exercise and fresh air. Do we have a deal?’

He smiled a little sadly and stood up, thanking me.

From the window, I watched him leave the building and wander down the street in the direction of the church.

My first patient. I knew it was going to be quite a challenge, but nothing could have prepared me for what eventually followed.

Suddenly, my practice took off. In the week following that first session with Nicholas, I had a consultation practically every day, and I confess that I gave little thought to his case. So when he turned up the following Friday I had to consult my notes hurriedly before I called him through.

He looked tired and drawn, and once again ill at ease. It occurred to me that there must be a woman involved in this, perhaps unrequited love; but, whatever it was, I suspected that having a woman as his psychiatrist might be something he was finding difficult.

The battered folder he put down in front of me looked suspiciously thin for a summary of his ‘unsettling experiences’ over a period of almost six weeks, and I began to doubt the wisdom of asking him to write them down. Perhaps a series of interview sessions would have induced him eventually to be more forthcoming.

I made no comment, though, and took the folder with good grace. As I looked up suddenly, I caught him looking at me, studying me, as it were, as though trying to make up his mind to trust me. It convinced me even more that there was a woman at the bottom of all this – ‘cherchez la femme’, as we say. He smiled to hide his embarrassment at being caught out, and I felt instinctively that I had passed some sort of a test for him, perhaps by not commenting on the brevity of the folder, and that he accepted me. It was a turning point in our relationship and I hoped his newfound trust would help him open up to me.

The manuscript was a huge disappointment. Even a cursory glance proved that. A series of dates and a short recounting of ‘facts’; it was just like a police witness statement – a report of an incident, ten pages of facts with no feeling, no personal observation, nothing at all to help me.

Deciding to test his confidence in our relationship, I pointedly closed the file, looked up at him and held his eyes, forcing him to look at me.

‘I’m sorry, Nicholas; this is not at all what I had in mind. It’s a legal dossier – a list of events; I want to know how you felt, what you thought, how you reacted. I want a blow-by-blow account of your emotions, your intimate perception of these events…’

He looked shocked that I should suggest such a thing.

‘Nicholas, I need to see inside your head. I’m a mind doctor, not a mind-reader: I can’t guess how you felt then, or feel now. You have to tell me. You said you wanted to be a writer, so use your talent, Nicholas, and don’t come back till you’ve written it all down for me.’

I knew it was a calculated risk; he might not come back at all. But I had to take a chance on that, or I could not help him.

I did not see Nicholas for several weeks. Nobody did. He locked himself away in his tiny flat in Rueil-Malmaison and – he told me later – just wrote and wrote until he had it all down on paper.

When he delivered it, his physical appearance so shocked me that I sent him back to Dr David for an urgent check-up; I thought he might be suffering from exhaustion. He was eventually persuaded to join some friends on a short trip to Italy.

It took me several hours to read Nicholas’s account, and it had a profound effect on me. At first, I thought it a romance, and then perhaps a crime thriller and, finally, a ghost story.

It follows here, in its entirety, with no changes except the correction of a few archaic grammatical expressions and slightly old-fashioned idioms. His French also contains one or two student slang expressions which I have changed to avoid confusion. Throughout his account, Nicholas has varied people’s first names, sometimes using the French form, i.e. Natalie, and sometimes the Russian, Natalya; likewise Serge and Sergei. I have seen no point in standardising these, as the sense is always evident. When unusual Russian words have been used, an explanation is given.

It is a strange and harrowing story.

Madame Lili

Her Imperial Highness, Princess Natalya

Nicholas’s Story

CHAPTER 1

Unrest

‘Ce n’est pas une révolution, Sire, c’est une mutation.’

; SLOGAN, MAY 1968

The few francs that I had were long since spent and a Métro ticket was out of the question; so when the tube stopped at Place St-Michel I dodged the automatic barrier by going through behind another student, glued to his back and barging him forward so as not to get caught in the closing door. He knew but he didn’t even turn round; I mean, we all did it in those days.

My mind was buzzing as we trooped up the steps of the exit. What would it be like, the Boulevard St-Michel, after nearly two weeks of student riots? Would the trees still be standing? Would the fountain be running? Would all the shop windows be smashed?

I was so lost in thought that I didn’t see him until it was too late and he’d seen me first. To go back down would have been too obvious, so I kept on up the steps and tried to look casual.

He was a few years older than I; twenty-six or twenty-eight perhaps, short hair, clean-shaven and wearing a very smart dark suit. It was a fine spring day in mid-May and the sun shone on the last few steps. But I felt a sudden chill.

I tried not to make eye contact but I could feel him looking at me, and when I came level with him on the top step he pushed his police ID right into my face. ‘Police nationale, monsieur. Sûreté. Renseignments Généraux!’ He paused for effect and then spat out the words, ‘Pièces d’identité. PAPIERS!’

Police checks were nothing new to me; unused to such things at home in England, I had at first found them daunting, but as a student in Paris I had soon become inured to the process. But today I was afraid. Afraid because my visa had expired, afraid because I had no money, and afraid because the police were far from happy with students.

‘Bonjour, Monsieur l’Inspecteur,’ I stammered, and made a gesture as if to search my pockets for the sacred ‘papers’. I needed to explain my situation as quickly as possible. ‘Vous voyez, monsieur, le problème, c’est que –’

The Spaces in Between

The Spaces in Between